This phrase, "Yet once more," indicates the removal of what is shaken-- that is, created things-- so that what cannot be shaken may remain. Therefore, since we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, let us give thanks, by which we offer to God an acceptable worship with reverence and awe; for indeed our God is a consuming fire.

Editors note: This passage above from the penultimate chapter of the Letter to the Hebrews struck me as the right introduction to what follows, which, as a piece of writing and art needs no introduction. But I offer one because I waited two years to publish it, wanting to find the right time.

Two years ago, there were vaccines for COVID-19 and a constant release of research figures. The U.S. surpassed 900,000 deaths. We had been without a bishop for a year, and it was a time for coming back to church while grieving loss. It was a time of reckoning with more than could be reckoned with.

Two years ago, the writer of this post had just begun to serve at the altar of our Cathedral. Some of us were reading Paradise Lost by John Milton (a far stranger book than I had imagined). Always ready to share poetry, Wendy read it too. Wendy is a visual artist, mental health counselor, and a friend of many years now. We both work with people while grappling with God and art. We share awe.

above: Thank You Fog for Lifting ( after Auden), 2021, mixed media on paper, 34” x 30”

Now is the time for this piece of writing, I think. We are heading into Lent. Soon we will celebrate the consecration of a new bishop who has moved far with his family to begin a new ministry here. This is a time of awe and joy, fear and gratitude, humility and hope.

A thing like awe that a cathedral is meant to inspire, holy fear is real. In the Bible pronouncements of angels are typically met with this response. Some of us run from God’s call like the prophet Jonah, becoming suffocated by daily ease as if swallowed by a whale. Some of us come to reckon with God after falling in love or the birth of a child brings beauty and terror of responsibility. Awe and fear come with the abundant life that comes from above when we say Yes to it. Here are Wendy’s words…..

Before it all began :

On Heavenly ground they stood, and from the shore

They viewed the vast immeasurable abyss. ( Paradise Lost Book VII,210)

Preparation for the feast. In a cold room with steaming ancient radiators I wonder how justice is served when lowly paupered souls attempt to give glory and honor. We dress the part. Later the holy ministers will wear vestments color-coded to the liturgy. It is not without some reverence and panic that I enter the back of the sanctuary to hear this sound…..the songs of angels. Waiting to light very tall candles in an orderly way on the altar is a feat. Preparation continues and then we assemble.

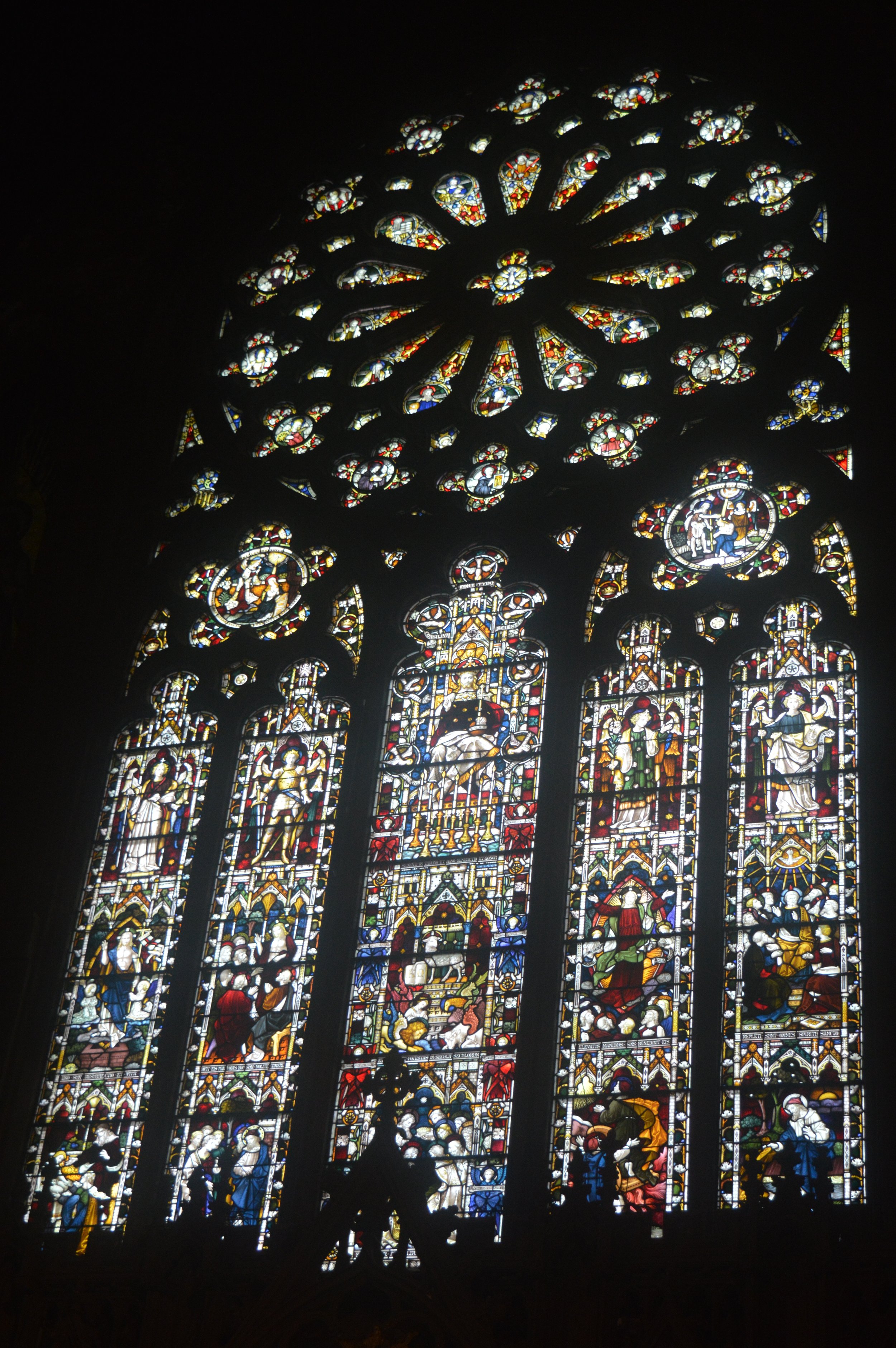

The stained glass window portraying St. Elizabeth is the highest point in the side chapel that I stare at longingly holding a crucifix that weighs more than I could have imagined. Under this window is an altar. At that altar the holy ministers prepare themselves for the procession while others take ready to support and at the same time feed on the unsaid prayers that are quietly being thought or versed internally.

I am acutely aware of the weight of the moment both literally and figuratively as I focus in on the hollow of Christ’s abdominal area that is carved as a circular abyss like shape in the wooden structure. I feel this as a punch in my own stomach. It is difficult as I become teary to the gravity of the gesture and the responsibility. The weight of the cross is real and I immediately sense the suffering and know, that just being there is enough and that Christ will accompany me in my own weakness which is real, caused not just by sin but by a weakness that wracks my body.

The waters have lifted up. O Lord,

The waters have lifted up their voice:

The waters have lifted up their pounding waves. (Psalm 93)

It is the first time I have truly identified with Christ on the cross despite being a doubting yet willing person. As a congregant I sensed this preparatory time in a different way. It is building an energy that is likened to a time of being seen for the first time, or in a different sense of time. Weddings and funerals, even ordinations share this as the time to behold the spectacle as it is given, formally and with reverence. I pray for strength silently as I know this is not an easy task.

In the assembling here I am also acutely aware of the importance of maintaining composure with piety. The experience is emphasized again sitting behind the ministers in choir after the procession. The draped vestment is carefully arranged over chairs as scripture and sermon are spoken and I feel the prayerful presence of The Dean who holds this quiet strength. I sense this. It buoys me to believe. The journey here is witness.

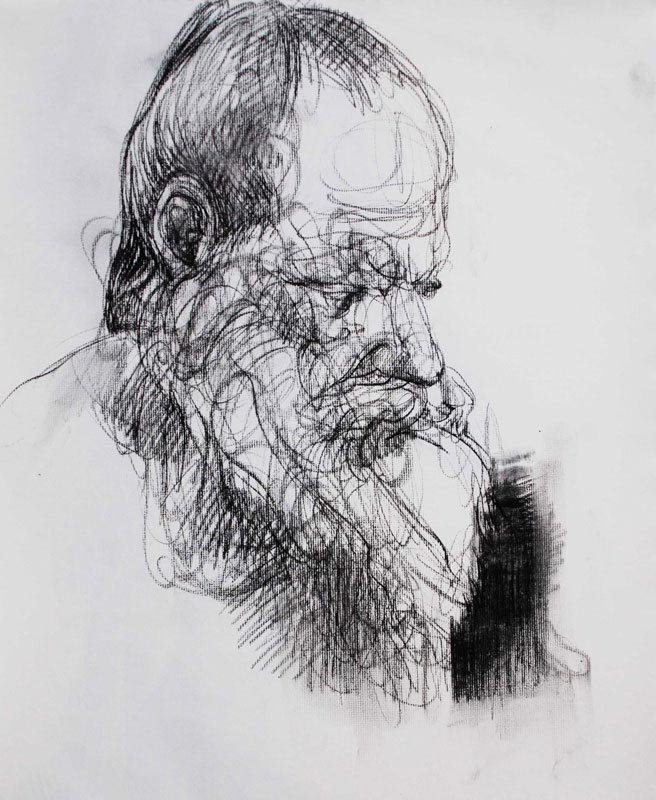

The Second time the reality of the difficulty, unlit candles, steps stumbled, strength summoned, still leaves me feeling like a Hollow Man gazing with doubt. I can be one person in this choreography defined and designed to summon deep concern for the kept rituals and reminders of the long path. So stepping lightly but firmly, remind myself that this is not about me or them, but Jesus on the cross.

The liturgy of Ash Wednesday will be celebrated at the Cathedral with the imposition of ashes on Wednesday, February 14 at 7AM, 12:05PM, and 7PM.

Please join me for Art of the Cross on Zoom on Tuesday, March 19 from 7:30PM for an hour of Lenten meditation with the art of Christ and His Cross. We will look at individual artworks as well as the symbol itself and its life in Christian history and imagination. Click HERE to register.